- Home

- Simon Butters

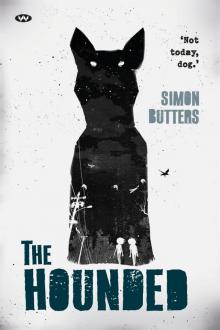

The Hounded

The Hounded Read online

Wakefield Press

The Hounded

Simon Butters is a screenwriter in film and television. His credits include Wicked Science, H20 Just Add Water and Mako: Island of Secrets among others. Simon lives in the Adelaide Hills with his two hilarious kids, a very busy wife, and a scruffy little dog that definitely doesn’t talk but does do a weird grunt when you pat her behind the ear. The Hounded, Simon’s first novel, was shortlisted for the 2014 Adelaide Festival Unpublished Manuscript Award.

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

www.wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2016

This edition published 2016

Copyright © Simon Butters, 2016

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Edited by Margot Lloyd, Wakefield Press

Cover designed by Liz Nicholson, designBITE

Ebook conversion by Clinton Ellicott, Wakefield Press

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Butters, Simon, author.

Title: The hounded / Simon Butters.

ISBN: 978 1 74305 186 3 (ebook: epub).

Subjects:

Young adult fiction.

Depression in adolescence—Fiction.

Mental illness—Fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

Wakefield Press thanks Coriole Vineyards for their continued support

For Penny, Zoe and Charlie. My light.

Chapter One

Alias: @The Full Monty

Date: Thursday February 14, 6.15AM

There’s something in my room. Time left to freak out: four, three, two, one …

*

I was freaking out. I don’t know how long it had been there but when I opened my eyes it was staring right at me. It was silent as night, the black dog.

I sat up in bed and squinted, trying to wipe away night’s lingering shadows. It had a long snout, a shiny black coat and deep, sorrowful eyes. Those eyes were empty pits; black holes in space and time. It held my gaze and I fell away, getting a sick feeling in my guts like I’d gone over the top on some killer rollercoaster. Stupid dog.

I thumbed out my bewildered status in SpeedStream and, as usual, nobody responded. This was the all-new, worldwide, social networking freeware that practically every teenager on the planet live streamed on their smart phones. I’d been on it for two months now, and had the grand total of three connections: one guy in New Zealand, one in Greenland and one guy from Germany who was I guess the closest thing I had to a friend, which was odd because he didn’t speak a word of English. We conversed by converting text into one of those online translation sites. Our conversations were like decoding a series of warped Chinese whispers. We were perpetually lost in translation.

Alias: @The Full Monty

Date: Thursday February 14, 1.25AM

I can’t sleep. I think it’s the full moon.

@Gutentag

I wouldn’t eat that if I was you being.

@The Full Monty

I don’t plan to. Besides, it’d need a lot of salt :)

@Gutentag

Must retire now. Pondering cheese limits my understanding.

*

What did I tell you? Totally random, huh? Still, I didn’t mind. I was connecting with someone; a real person, no matter how far away, had attempted to share their innermost thoughts with me. That was worth something, even if it was just nonsense.

The dog?

I thought maybe it was a birthday present. It was my fifteenth birthday, so it was possible, I guess. Mum and Dad could have slipped it into my room during the night. Deep down, though, I knew better. Besides, the dog looked too old. Normal people gave each other puppies; something cute and innocent to care for and give wise instruction to. This creature looked as old as time. The thing just sat there and looked at me. No expression. No playful wagging tail. Nothing. It had to be a stray.

It wasn’t unusual to have a stray animal suddenly appear in our house. This sort of thing had happened before. Once, a feral cat took up residence in my mother’s underpants drawer. How it got in nobody knows but it had kittens in there. My mother was furious. All her undies were in there, soiled by the gross bits that come out when an animal has babies. It was a nasty cat, that feral cat. It hissed and growled and threw its paws about when you walked down the hallway. It was crazy. Its eyes were wild and the noise that came out of it was the sound of pure insanity. I loved that sound. I’d walk past the open door, goading it to scream and yowl at me one more time. My mother hollered at me to leave it alone. We had to wait until my dad finished work and came home to scare it out. He took one look at it, and raced at it carrying a cricket bat. It took off out the window, leaving its kittens mewing away, helpless. Why it chose to have its kittens in my mother’s undies remained a mystery. Maybe it knew it wasn’t cut out for motherhood and left them there in hope we’d care for them. The next day they were all gone. There was a fresh hole filled up in the garden. I would have liked a kitten.

I ignored the dog and shuffled past it to the loo, passing my reflection in the mirror. Things today were bad. I’d grown a zit the size of a walnut. Okay, maybe not quite the size of a walnut, but it was big. It shone a brilliant, painful red.

In the rest of nature creatures painted in such a fierce colour are considered dangerous, filled with some kind of toxic venom, like red-back spiders, or those yellow frogs from the Amazon that lost tribes used to make poisoned darts. Me? I wasn’t considered dangerous. I’d just get punched out. There’d be no way to keep a low profile with that throbbing red light on the end of my nose.

The rest of me didn’t fare much better. My hair was mussed up from another sleepless night and my teeth were in dire need of braces, a luxury my family could never afford. Teeth grew out of my mouth at awkward angles. The older I got, the more twisted and shameful my smile. I grinned in the mirror and repulsed myself.

I had taken a vow never to smile in school photos. Everyone always blamed me for ruining them because of my sullen expression. They had no idea I was doing them all a favour, sparing them the sight of my rancid set of chompers.

It wasn’t always this way. I used to be quite good-looking as a kid. I was even in a glossy brochure once, selling bicycle shorts for a local sports store. That was the first money I’d ever earned. I never saw it of course; it was gone before we even got home, replaced by cartons of cigarettes. My mother smoked them in quick succession: two, then three at a time. The cigarettes poked out of her face like giant fangs. I hated cigarettes. I could always smell her charred insides from across the room. The scent of burning lung was ever-present in our house. Whenever you walked in the lounge, you’d disappear into a dense fog hung with the sickly, sweet smell of decay.

The mirror bent and swayed, mocking me. My chin had a little bit of teenage growth on it. My first real whiskers had erupted out of me, daring to enter our world. They were malformed at birth, so thin and delicate they’d practically blow off in a good wind. Other kids thought their first whiskers signalled their ascendancy into adulthood and took to shaving, more in an effort to promote further growth than to look tidy, I guess. Me? I didn’t bother with shaving. Mine were so downy and pathetic I could just rub them off with the back of my hand.

I was a skinny kid. My cheekbones sunk. Ribs protruded out my sides. I don’t remember when controlling the urge to eat started, but I had limited my food intake for years, I guess. Don’t get me wrong. This

was no sort of pathological disorder, I was sure of that. I could eat if I wanted to. I just didn’t want to. It took an enormous, concentrated effort of will. My mind and body were at constant war over the subject. My brain had to force my body into submission. It was a daily chore to ignore nourishment, to forget chocolate existed, to wipe the memory of vanilla ice cream from my mind. Something in me enjoyed the sacrifice, I guess. It made me feel stronger, the weaker I became. I thought I was in control. I was an idiot, of course, but I didn’t care.

The dog watched me as I dressed for school, putting on a pair of faded jeans and a dirty t-shirt from the day before. I was slightly annoyed now that it hadn’t gone away.

‘What do you want? Go on. Get!’ I snapped.

It sat there impassively, watching me squeeze my face in the mirror. The zit refused to pop. It stubbornly held on to its bonanza, preferring to ambush me at some later opportunity. The dog maintained a silent vigil. From its curious expression, I half expected it to laugh. But it just sat there, staring into me.

I went to the kitchen and allowed myself breakfast. Today’s ration consisted of a quarter slice of toast with one smear of jam in the corner. I concentrated my efforts and imagined a banquet before me. If I had enough determination, I could get through the day without anything further.

The dog didn’t beg or anything. It didn’t slobber on my leg looking for a bit of toast. It hadn’t even wagged its tail yet. It just sat and watched. I tossed it a chunk of toast. The dog glanced down and I was sure it rolled its eyes in disdain.

The crust dropped to the floor to find itself among friends. Years worth of breadcrumbs were taking up residence down there, unswept, threatening to create an ecosystem of their own. Those crumbs might clump together, I thought, to one day form little planets made entirely of crumbs. And on those little crumb planets, maybe a whole new civilisation of tiny creatures would evolve. One day, they’d become so advanced they’d send up little spaceships to explore their universe and come to the startling conclusion that they were all just crumbs. They were nothing but some other person’s refuse, left lying on their kitchen floor. This shockwave of self-doubt would send their world into anarchy. Riots would break out. Governments would fall. A once proud and intelligent race would succumb to the crushing realisation they were nothing more than a bunch of worthless crumbs. The dog ignored the toast.

‘What kind of dog are you?’ I asked.

‘Black,’ said the dog.

I choked. Unless I’d just suffered a brain injury, I heard the dog speak. Now at this point I had a choice to make. Various possibilities exploded in my mind like a mouth full of popping candy and Coke. Talking dog? Hmm. Okay. Scientific miracle, secret government experiments, genetic mutation, alien body snatcher, my ear canals could simply be full of wax, could be a dream, god is dog spelt backwards, maybe I’ve been hit by a car and I’m in a coma, maybe I’m just …

‘No, you’re not crazy. Not yet anyway,’ said the dog.

‘Don’t you like toast?’ I asked.

‘If you’re planning to make this hard on yourself, keep that up. I don’t mind. I’m very patient,’ it warned.

My mother burst into the kitchen in her usual frenzy of cigarette smoke and worn out slippers.

‘Someone’s been in here! And moved the toilet paper!’ she bemoaned.

A complaint like this wasn’t unusual in our house. My mother was dead-set certain someone had sneaked in the previous night and moved the toilet paper. There was none left in the loo and none under the sink in the laundry. That was strange because she swore she just bought a new pack the day before. The only possible explanation was we’d been burgled. Some diabolical man had invaded our house, crept past our sleeping bodies in the dead of night with the sole intention of moving our toilet paper.

The fact that he’d left all our valuables where they were—Dad’s wallet, Mum’s antique jewellery—didn’t mean a thing to my mother. She was certain someone was playing tricks. She looked under the kitchen sink to discover the offending pack of toilet paper, hiding there all along.

‘Ah-ha! See? Someone’s been in here!’ she cried.

I grew up with this sort of thing on a regular basis and used to wholeheartedly believe that if you lost anything, it meant that some stranger had come into the house to move it about, just to annoy you. I pictured this evil wretch, delighting in his latest trickery. He’d have a black cape, a long moustache and sit outside the house wringing his hands in pantomime glee, listening as his latest Machiavellian plot came true.

It was only about two months ago that I finally realised my mother was just making all this up. In her mind, she couldn’t cope with not remembering where she’d put the toilet paper, so she invented this strange burglar guy to explain the mystery. Smart really. The idea that you could create someone so real that other people around you believed in him too astounded me. You just had to believe in them so much, there couldn’t be any reason to not believe in them. Sure, I was annoyed at myself for not waking up to this sooner but, to tell you the truth, I was in awe of her inventiveness. I continued the ruse. I didn’t do this to placate her. We just had an unspoken rule, I guess. Judgment was never allowed.

‘Yep, he’s getting trickier Mum,’ I offered.

She lit up another cigarette, breathed in her breakfast, and made her way back to the loo. She walked out without any mention of my birthday.

That was actually quite normal in my house. My parents hadn’t mentioned birthdays since I was six. They never told me why, but I figured they thought birthday celebrations were for little kids. By age six they must have deemed I was old enough to celebrate birthdays on my own. Either that or they’d just plain forgotten how to parent. Maybe both.

More disturbing than not mentioning my birthday, was the fact that my mother hadn’t mentioned the dog. Its impassive stare gave me the creeps but, at the same time, its presence felt somehow warm and reassuring. I knew this creature intimately. It knew me too. We were like old friends reuniting after a lifetime apart: a century lived of war, love, torment and joy, only to come together again at the final hour. This strange creature understood me. But as I looked closer, the dog began to shift and change. The longer I looked at it, the less it seemed like a dog at all.

I squinted, trying to exorcise it with my mind. My eyelids shut out the world. Everything fell away and I travelled to some other space, some other time. I floated there, in that shadow world. I lost my arms and legs. My body merged with the nothingness. I was free.

If you haven’t noticed by now I suffer from some kind of affliction. My mind tends to wander. I don’t mean this in the figurative way, like I’m constantly daydreaming, although most of my teachers believe this is the case. I mean it in a very literal way. My mind actually wanders. It leaves me. Sometimes for hours.

It can happen anytime, anyplace. There’s no trigger, no rhyme or reason, it just happens. I have no control. It’s like an out-of-body experience. I’m on autopilot. I could be just about to cross a busy road, or discover one of humanity’s enduring secrets when my mind will simply disappear. My eyes roll back into my skull. The world around me fades. A numb feeling spreads all over my body. I have no sense of touch, no sense of taste. Nothing. I can still see and hear, but that’s about it. It’s as if my head has suddenly been separated from my body. I am decapitated, and my mind dropped into a jar of thick jelly.

Meanwhile my body is left to its own devices, left standing like a headless shell. To its credit, my body will often try its best to run the show while I’m gone. It will often walk me around like some kind of zombie, pretending to still be a part of the living.

Once, when I had to stand up in front of the class to give a talk, I got sidetracked by one of life’s multiple tangents and my mind abandoned me for over thirty-five minutes. There I was in front of everybody, drool hanging from my mouth, eyes rolled up at the ceiling. People giggled. Someone threw a blunt object at my head. Nothing brought me out of my stupor.

/> Eventually my body got so annoyed, it decided to give this thinking thing a go. It couldn’t be that hard, after all. My actual brain hadn’t done that much to impress it, I guess. My body tried to force me to speak. But without a brain to formulate any thoughts, the best it could do was mimic actual words. My jaw hung open and my tongue flapped about, but all that came out were some weird barnyard sounds. I moaned and groaned and everybody stared. More blunt objects.

Somewhere, off in the distance, my mind watched on. I could hear the sounds, but they sounded far off and alien. No matter how much I concentrated, I couldn’t understand what I was saying. From the expressions on everyone’s faces in the classroom, they couldn’t understand what I was saying either. Was I even speaking English? Or was I just standing there mumbling incoherently? I had no idea. Eventually, I fluttered back into my brain and took the wheel over my rambling tongue. Suddenly the words became English again. Somehow, I always made it back to my body before anyone called the police, or an ambulance, or worse, my mother.

So there I was with the dog in the kitchen, my brain in a jar of jelly.

‘Are you still with me, Montgomery?’

Okay, stop right there. Yes, my name really is Montgomery. But everyone calls me Monty for short, which is just as bad really. My mother, seconds after she’d given birth, decided to call me Montgomery in a fit of idiocy. It was only six months ago that I understood why during sex education. When mothers give birth it’s really painful so the doctors often give them so many painkillers they don’t know which way is up. Yep, my mother was drugged out of her mind when she decided to call me Monty. My father was apparently confused at the time.

‘Didn’t we decide to call him Bob?’ my dad had muttered.

‘No!’ wailed my mother, writhing about like Medusa with her snakes cut off. ‘He’s Montgomery, can’t you see? Montgomery! I’ll never forgive you if we don’t call him Montgomery. The world will end if we don’t call him Montgomery!’

The Hounded

The Hounded